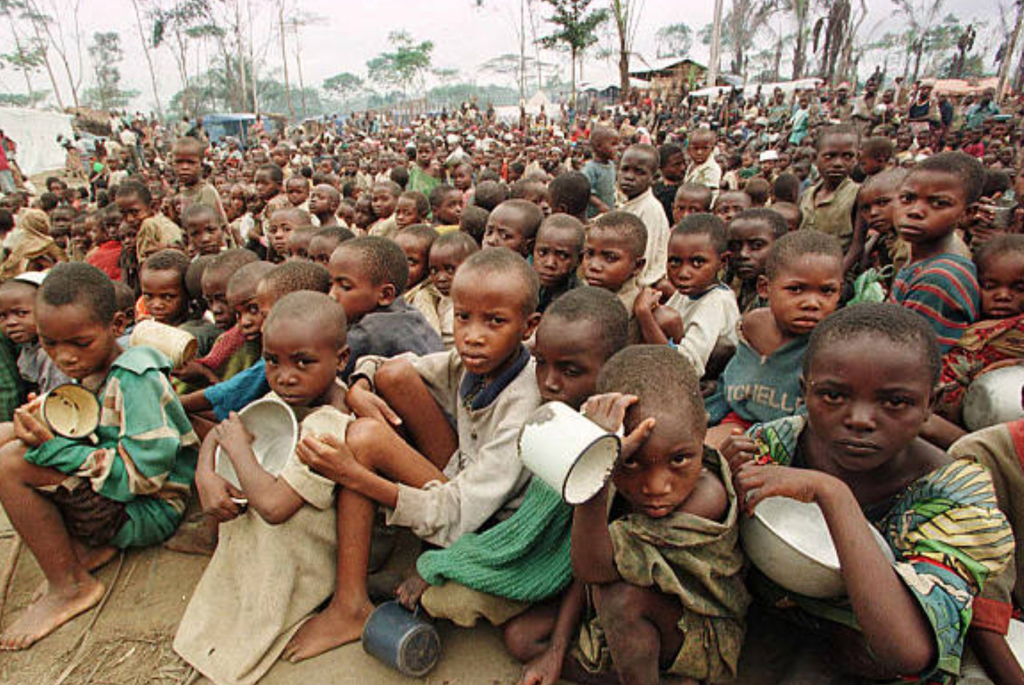

During the visit of UNHCR President Sadako Ogata to the Tingi Tingi refugee camp, a heartrending scene unfolded before her – over 50,000 children, seeking refuge from the harrowing RPF Hutu massacre, stood as testaments to the brutality they had endured. These children, tragically, were largely orphans, robbed of their parents by the unrelenting RPF offensive. Despite this overwhelming display of human suffering, Sadako Ogata’s response was to depart, leaving these innocent lives to fend for themselves within the unforgiving forest. Captured in a powerful image, these young souls clung to a banner bearing a chilling message: “More than 20 children die every day.

Dr. William A. Twayigize

- Home

- About Us

- Testimonies

- The Long Walk

- My Homeland

- A Day With My Father

- The Village Traditional Healer

- A Murder On Boxing Day

- My Last Football Match

- Our Prophets And Patriarchs

- The Assassination of the Presidents

- The RPF Massacres of Hutus in Zaire/DRC

- The Fall of Mobutu

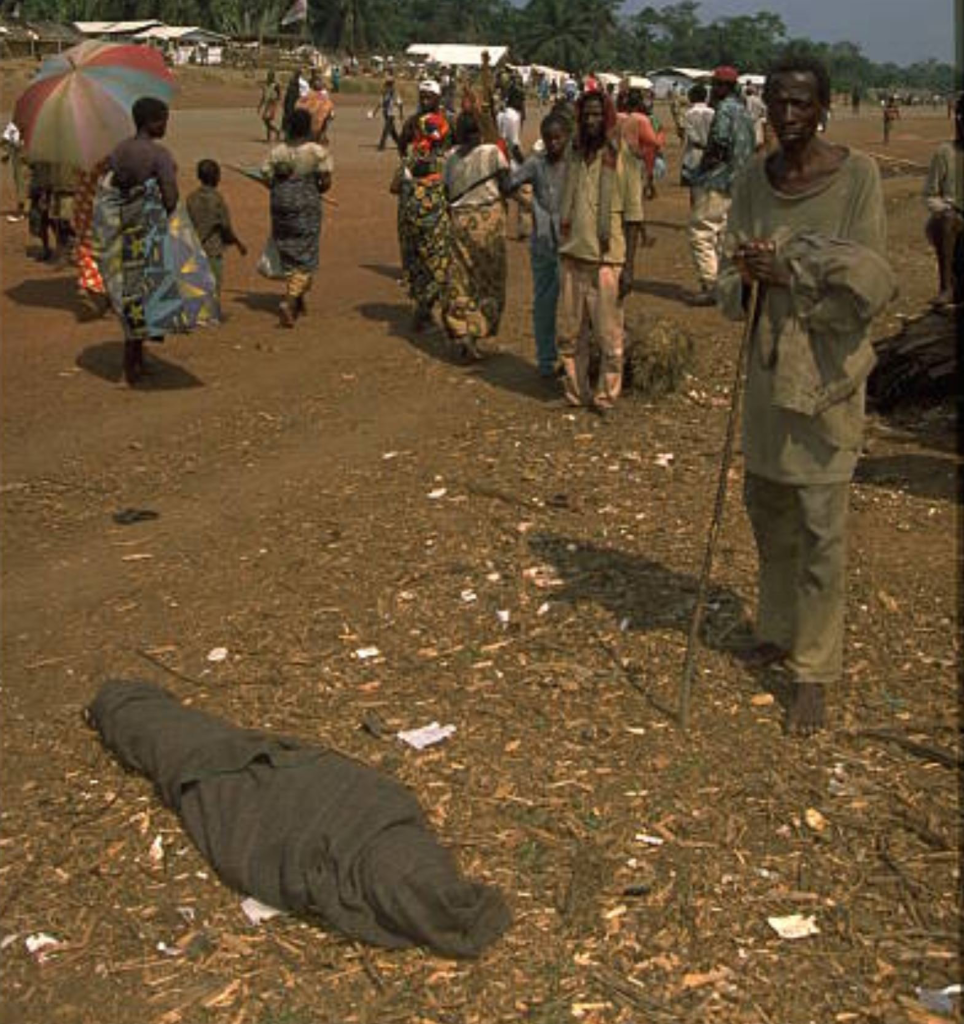

- The Hutu Refugees Massacres in Picture

- A Hellish Journey to Rwanda

- Killed From The Altar

- The Origin of Hatred

- Arriving In Kenya

- A Scarred Past

- Coming to America

- Arriving in America

- Ministries

- Contact Us