In this photo, MONUSCO, the United Nations peacekeeping mission, is inaugurating a police station in Walikale. However, for many Congolese, MONUSCO has become a contentious presence in their country, seen as a stumbling block due to allegations of involvement in resource exploitation. Calls for the UN to withdraw from the DRC are met with resistance, often led by nations like the USA and UK, who advocate for extended peacekeeping missions. This has fueled frustration among the Congolese, who perceive the UN as complicit in the exploitation of their country’s resources. The UN’s failure to protect civilians during rebel attacks while actively engaging in regions rich in minerals has deepened this resentment. Additionally, accusations of sexual abuse involving UN peacekeepers, including minors, have gone unanswered, further eroding trust in the organization.

Dr. William A. Twayigize

- Home

- About Us

- Testimonies

- The Long Walk

- My Homeland

- A Day With My Father

- The Village Traditional Healer

- A Murder On Boxing Day

- My Last Football Match

- Our Prophets And Patriarchs

- The Assassination of the Presidents

- The RPF Massacres of Hutus in Zaire/DRC

- The Fall of Mobutu

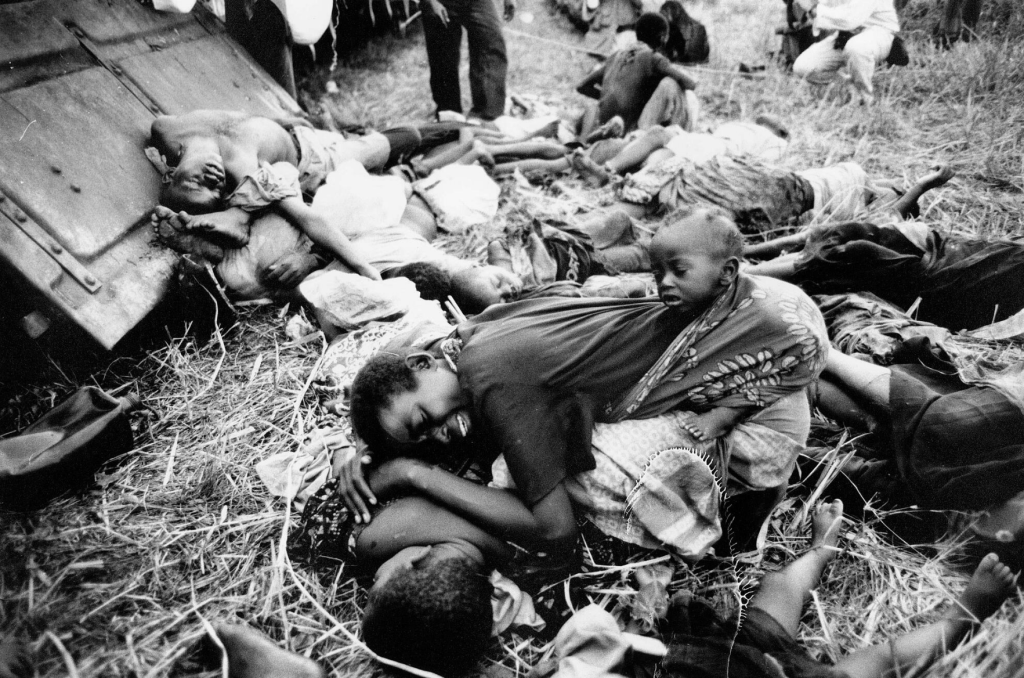

- The Hutu Refugees Massacres in Picture

- A Hellish Journey to Rwanda

- Killed From The Altar

- The Origin of Hatred

- Arriving In Kenya

- A Scarred Past

- Coming to America

- Arriving in America

- Ministries

- Contact Us