As I observed others completing their meetings with the pastor, I knew my turn had come. I entered his office with a pronounced limp, my backpack hanging from one shoulder, and my weight heavily supported by crutches. My throat felt parched, and my attempt at conversation was a mix of broken English and Kiswahili. Despite my limited language skills, we managed to engage in a brief exchange. I began by explaining that I was a refugee from Rwanda, having endured brutal torture that left my legs riddled with fractures and fresh wounds. I had just arrived in Kenya, a mere four hours ago, seeking assistance from the church. I emphasized that the church was my sole source of support in this unfamiliar land, as I knew no one else in Kenya except for a friend who had once worshiped at Karura SDA Church, and it was upon his recommendation that I sought help here.

However, for reasons that remain a mystery to this day, my words seemed to trigger an inexplicable agitation in the pastor. His eyes blazed with an intense rage, and his irritation surged uncontrollably. As my surroundings blurred into darkness, a suffocating dread settled over the room. Fearing that the situation was spiraling dangerously out of control, I hastily retrieved the letter from the Rwankeri SDA Conference and extended it to him, desperately hoping it would ease the mounting tension whose origin eluded me. To my profound dismay, not even this letter from their sister church in Rwanda could quell the storm that was brewing within him. In a sudden eruption of anger, the pastor abruptly rose from his chair and advanced menacingly toward me.

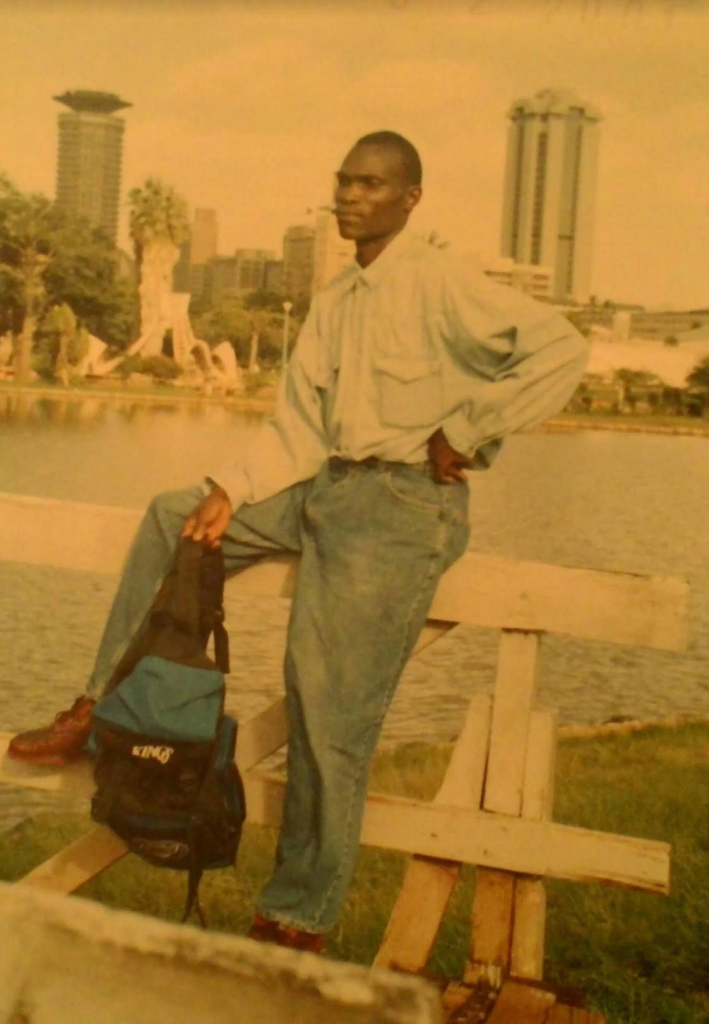

My eagerly anticipated encounter with the pastor, in whom I had placed my hopes as a desperate refugee, took an unforeseen and nightmarish turn. Inside the dimly lit office, my words seemed to kindle an unexplained inferno within him, transforming his once light-skinned countenance into a visage of seething rage. Before I could fathom the source of his anger or even extend an apology, he unleashed a ferocious storm of violence. With callous disregard, he seized my crutches and backpack, hurling me from his sanctuary as if I were discarded refuse, condemning me to the harsh embrace of the unrelenting concrete below. My legs flailed helplessly, my crutches somersaulted through the air before landing in a nearby cypress fence, but providence intervened to spare my head from a brutal impact, all thanks to the backpack that served as an unexpected cushion. Stunned and bewildered, I bore witness to the pastor’s eyes ablaze with wrath, a stark contradiction to the serenity I had envisioned in his sanctuary. The bewildered secretary, frozen in disbelief, watched the shocking spectacle unfold, and to her surprise, one of my shoes descended from the office roof, where it had been flung by the force of my impact on the concrete ground. Meanwhile, onlookers, later identified as being from Kisii, stood in horrified amazement, grappling with the enigma of what had provoked this explosive outburst. The pastor’s bitter words, “We don’t want refugees in this compound! We are not UNHCR! Go to UNHCR!” hung in the air, leaving me shaken and disoriented, plagued by hunger, thirst, and a head still spinning in disbelief at the abrupt and shocking turn of events, as I grappled with the stark reality that my day had unraveled so dramatically at the hands of a pastor.

After this incident, when kind-hearted individuals extended their help, a multitude of thoughts swirled in my mind, pondering whether I had encountered a true pastor or someone else entirely. In those moments, two poignant scriptures from the book of Matthew came to my rescue. The first was from Matthew 7:15, where Jesus admonished, “Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.” The second, from Matthew 7:21-23, echoed in my thoughts, “Not everyone who says to me ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven.” Despite the pain and disappointment I experienced, I chose to anchor my faith in God, seeking His guidance and strength to navigate through such challenging situations.