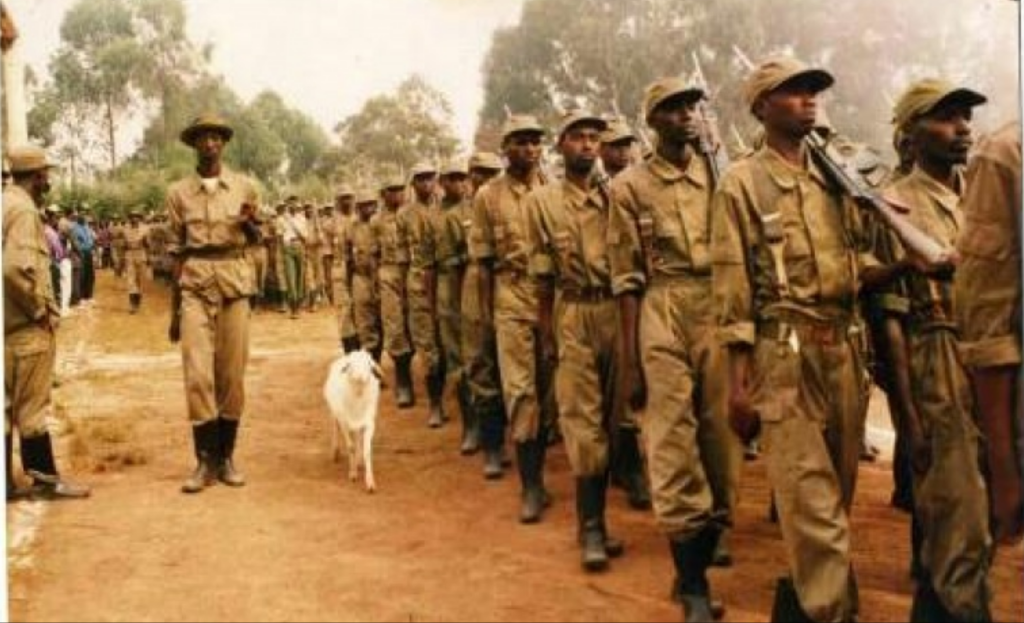

At the Ingando training sessions designed for teachers, Gen. Kabarebe delved into the narrative of a white sheep, which held a pivotal role in the RPF’s 1994 strategies for the Kigali assault. This unique sheep didn’t merely stand on the sidelines; it actively participated in military parades. Acquired from an Ethiopian witch doctor, the sheep was marked for sacrifice, seen as a crucial step towards securing the Tutsi rebels’ triumph in Rwanda. However, Gen. Kabarebe’s legacy is tainted with dark allegations. Prominent human rights organizations accuse him of orchestrating the mass extermination of Rwandan Hutu refugees and the Congolese in DR Congo in 1997.

Dr. William A. Twayigize

- Home

- About Us

- Testimonies

- The Long Walk

- My Homeland

- A Day With My Father

- The Village Traditional Healer

- A Murder On Boxing Day

- My Last Football Match

- Our Prophets And Patriarchs

- The Assassination of the Presidents

- The RPF Massacres of Hutus in Zaire/DRC

- The Fall of Mobutu

- The Hutu Refugees Massacres in Picture

- A Hellish Journey to Rwanda

- Killed From The Altar

- The Origin of Hatred

- Arriving In Kenya

- A Scarred Past

- Coming to America

- Arriving in America

- Ministries

- Contact Us